11.03.2014 - 09:16

[Translator’s note: Though the Madrid bombings of March 11, 2004 dominated headlines worldwide, few people outside of the Spanish State know the story of how the Spanish government, headed for reelection just three days later on March 14, tried to manipulate the outrage of the people by pinning the blame for the Al Qaeda attack on the Basque group ETA. In this article, editor Vicent Partal explains the role of VilaWeb and the nascent social networks in getting the truth out.]

The way it felt on March 11, 2004 is hard to forget. First thing in the morning a series of bombs had exploded on commuter trains arriving in Madrid. The Basque president Juan José Ibarretxe, an unlikely candidate for favoring the Spanish ruling Partido Popular, had held a press conference—his was the first!—and had roundly declared that the attacks had been carried out by the Basque group ETA. So roundly that he puzzled a lot of people, including the reporters in VilaWeb’s newsroom on Tàpies street. The reporters from the El Punt Avui who worked on the second floor of the building had not yet arrived. And so, at that early moment, the questions and nerves were ours and ours alone. And as our friends from the other paper trickled in over the morning, they passed by our offices in the basement and each one, without exception, asked the same question, ‘Can you believe it?’

It wasn’t a question of believing it or not. The reaction of José Aznar’s PP government to the attacks, we know today, had been obscene in the extreme. All of the TV stations repeated that the death of dozens of people—at that point we still didn’t know how many—in a rash of simultaneous attacks—we still didn’t know how many—was ETA’s doing. The early digital editions of the paper media said the same. And the whole thing unleashed waves of indignation that came to us every which way possible: email, SMS, phone calls. The atmosphere was unreal. And still…

And still, it didn’t make sense. It was too hard to believe. We said it over and over again while we looked for explanations. ‘It’s not logical.’ Opinions arrived from other newsrooms, from people who had gone through a thousand battles, who weren’t sure about it either. Overwhelmed and confused, I sat down in the stairwell to call Martxelo Otamendi, the director of Berria [a Basque newspaper], and other personal contacts I have in the Basque Country. ‘I don’t know if I don’t believe it or if I don’t want to believe it,’ he told me with that professional honorability that is so characteristic of him. Everything was so strange…! We were living events that they wanted to present to us in a certain way, and we just weren’t able to see it. And it was clear that the whole thing would explode, in one way or another. We felt like we were inside a historic cataclysm, but we didn’t yet know which one.

A telephone call from London

The phone rang. I think Pau Pertegaz picked it up. It was a reader who was calling us from a phone booth in Heathrow airport to tell us that the British police were on high alert ‘because of the Islamist attack in Madrid’. We don’t know that reader’s name. We didn’t write it down and we never thanked him. But he opened our eyes. The police in London don’t go on high alert over Basque bombings. Here was the first piece of verifiable evidence that didn’t fit. That, and the declarations of the British Interior Minister who confirmed the alert.

Some parts of the situation were just surreal. For example, we had to go to the website of the Argentinean newspaper Clarín to read what Batasuna [Basque pro-independence party] thought about the attacks. Their opinion was important but not a single television station, news agency, or traditional paper was covering it. Arnaldo Otegi, Batasuna’s leader, had to speak to an Argentinean paper so that we could find out what he thought about it.

It was amidst this whole atmosphere that we cleared off one of the newsroom tables in order to spread out a huge piece of white paper, that we divided into four columns: ETA, ETA-Armagh (which represented a possible new violent schism off of ETA), Anys de plom (Lead years, in case this was an ETA attack directed by the state), Al-Qaeda. All of us brainstormed reasons for and against all of the possibilities. That there were so many casualties and that there had been no warning didn’t fit ETA’s modus operandi. That it was the 11th fit with a Jihad attack… And so on, question after question. Slowly.

As the minutes went by, however, and more and more, the Al-Qaida column was filling up with motives and reasons and attracted more attention. Montserrat Serra still remembers today how special and intense it felt. It was a moment that we were all wracking our brains to try to get clear about what was going on.

The most important editorial

Around midday, with our ideas slightly more in order, we decided it was time to publish an editorial and say something. At that time, at VilaWeb editorials were more sporadic, not published every day like now. But the overriding feeling was one of absolute indignation against ETA and against everything and anything remotely close to ETA and surely for that reason we felt, with every passing moment, the weight of more and more doubts. On TV they were saying things that were impossible to repeat and from the Basque Country we were getting a palpable feeling of fear, that they were going to have to pay a very high price for the deaths in Madrid. But logic, and common sense, were pointed in a different direction and we felt obligated to explain it.

Here’s the editorial, just like it was published. And the fear that it transmits, beyond what it tries to explain, is obvious. In the first paragraph, you can feel the tension from just having explained something elemental: we have the right to ask questions. That first day, there were only suspicions. And then at the beginning of the second paragraph I wrote, “This attack is probably the work of ETA. But it’s unusual. ETA has never attacked this way.” Three sentences: the first and two more that contradict the first. Three sentences that indicate to what extent things were clear to us, but that, in that rarefied atmosphere it was very, very difficult to openly question that ETA had not been behind the attacks. And that is what we were doing, exactly what we were doing, in that piece.

A piece in which, after analyzing the other options, we finally openly exposed the arguments in favor of the thesis that the attackers had been Al Qaeda:

“—the fact that the bombings happened simultaneously, which is characteristic of Al-Qaeda

—the high death toll. Never, had ETA caused even a remotely similar number of deaths, nor had it placed so many bombs at the same time

—Islamic Algerian groups had perpetrated similar attacks in the past in the commuter and subway trains in Paris

—Aznar’s support to Bush and Blair’s after the September 11 attacks had put Spain on Al Qaeda’s enemies list, and Bin Laden himself had spoken about it

—part of the operations for the September 11th attacks had taken place in Tarragona and Madrid”

Seen from a distance, ten years later, that editorial can even seem a little cold. But many people, even to this day, remember it as the piece that made them doubt, and it is possibly the most important thing we have ever published at VilaWeb to this day. It offered the readers a view of the facts that was very difficult to reconcile with the huge propaganda operation that the Aznar and Rajoy government had put into motion. And it asked readers to calm down and apply reason. Nothing more, nothing less.

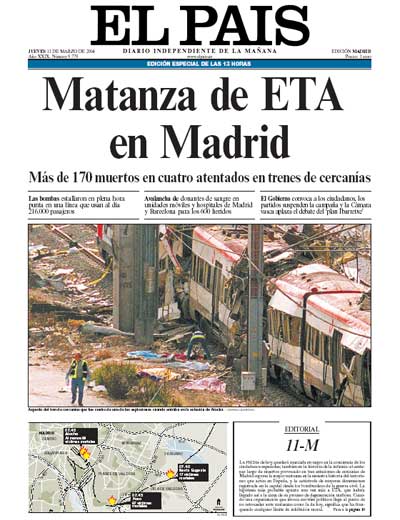

The newspapers at the stands all fingered ETA

The reaction was enormous and took us by surprise. But it wasn’t easy. I still save some emails that accused us of ‘turning our backs on the dead’ among other insults. I have to say, I think that’s normal. There have been few times that my legs have shaken like they did when, a little while later, Assumpció Maresma and I took a short walk to think out loud and clear our heads. Our steps brought us to the Rambla, where we took a look at the special editions of the newspapers, of El País, of El Periódico, who declared without a shadow of a doubt that ETA had carried out the massacre. Not even ten hours had gone by and their definitiveness was surprising.

Antonio Franco, El Periódico’s editor at that moment, has since given all manner of explanations about what happened and has acted with notable elegance and self-criticism. The Madrid paper, El País has not. As it is well known, at least now, José Maria Aznar [Spain’s Prime Minister at the time, whose bid for reelection was to be held just three days later] personally called them to tell them that it had been ETA and backed them against the wall in way that is hard to repeat. The result was headlines and front page editions that cannot be shown in public without giving complicated explanations and that El País, for example, has hidden for years and even tried to erase from Google.

We went quickly back to the newsroom, genuinely afraid of the consequences of what we had just published. But the news kept coming with new clues. And a few hours later, at exactly 8:20pm, we decided to publish VilaWeb with a definitive headline: “Al Qaeda claims responsibility for bombings in Madrid in the Al-Quds paper“. (Note: the copy of this article that is in our archives incorporates fragments of news that were published on later days because in 2004 we were still not aware of the importance of maintaining an archive, and it was common practice for us to write new articles on top of old ones.)

The headline spread more than we had ever seen a headline spread on the web. We weren’t aware, but between that Thursday and the following Sunday everything was going to change. The political persuasion at Spain’s helm, and surely, in the long term, at Catalonia’s. And journalism. Zapatero [the PSOE leader who beat Aznar in the elections on March 14, 2004] says that he knew he was going to win, but there is precisely no one who believes that. The truly abominable manipulation that the Partido Popular’s government attempted came out very badly for them. And that is because the old newspapers and the controlled television stations were no longer alone.

The deception was unsuccessful because it was impossible to keep up and because the role that the traditional media were unable to play was played by us—new media and social networks—for the first time. VilaWeb’s publisher, Assumpció Maresma, still remembers the shock she felt when she overheard a taxi driver telling someone on his phone to go to VilaWeb’s website ‘because they’re explaining what’s really going on’. The 140,000 readers that visited VilaWeb on March 11 made a record that went undefeated for many years. And that was still in the day when internet connections from people’s homes was still pretty low.

And, in the same way that I remember with trepidation the newspapers in the kiosks that first midday, I also remember myself on the following Saturday watching the television in our colleagues’ El Punt office when the then Spanish Minister of the Interior, Acebes, finally recognized that they had found ‘a van with cassettes filled with Islamic verses’. The Spanish government had previously admitted the existence of an Islamic clue, but this was definitive. When I think of the dead, I regret having done it, but at that moment, I raised a fist in satisfaction: it was possible to defeat that huge orchestrated lie.

The huge role of cell phones

It was a defeat in which a variety of websites played a key role. But it was cell phones, especially the cell phones, that made all the difference. And concretely it was text messages (SMS), each of which ended with that historic “passa-ho!” (pass it on!).

Looking at it from the current era of Whatsapp, Bambuser, YouTube and Twitter, text messaging and its capacity for communication brings us back to the stone age. But it had an astounding effect during those three days, as Manuel Campo Vidal and Manuel Castells’ documentary, ‘The revolt of the cell phones’ [La revolta dels móbils], explains (Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3).

In a completely spontaneous way, via text message, March 11 created the first viral phenomenon in the history of communication in Europe. And that, in the end, toppled a government. Aznar could speak and threaten newspaper publishers and editors but he didn’t know that the threat came from another direction. As primitive as they were, and though they were still sent individually, one at a time, you would get waves of text messages from friends and acquaintances saying that the version offered by the traditional media was false. The fact that Al-Qaeda had claimed responsibility for the attack, that Bush had said on CNN that he was sorry if Spain’s participation in Iraq had caused this. That we had to go out on the street and demand the truth and that the PP government had used the attacks to win the elections. That…

Finally, everything lead to what at VilaWeb we called a ‘democratic revolt’. Thousands and thousands of people went out on the street banging pots and surrounding the main offices of the Partido Popular. Indignant. The police began to insinuate that they had been used. The opposition demanded explanations, now with a firm voice, and the PP began to sink under the weight of their own lies. At VilaWeb we made two editions of the paper in PDF format that many people printed out and distributed on the street. The first one on the 12th in the morning, after José Maria Aznar’s apocalyptic press conference. And the second, after the elections, directly explaining why Zapatero had won: “March 14, the price of a lie”.

It was a close call, though. Undoubtedly, with twenty-four hours less margin, the PP would still have won the elections and Rajoy would have become, then, the president of the Spanish government. But, in the face of a completely new phenomenon, those responsible for the fiasco and for the lie were unable to resist the pressure from the street, and for the first time, from the social networks.